Nashville’s north side had it all going on in the late 1950s. Jefferson Street was jumping with students from Fisk, Meharry Medical College, Tennessee State, and American Baptist Theological College. The clubs along the strip between Fisk and TSU were packed with kids out to hear Jimi Hendrix, Little Richard, Tina Turner, and Ray Charles. The post-WWII economic boom had brought new prosperity to the entire country, and teenagers, black and white, bopped to the beat, self-identifying as part of a new, hipper culture.

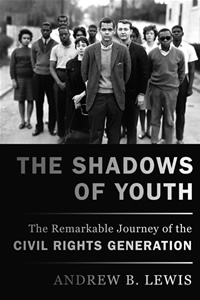

In that electric atmosphere, a group of earnest and thoughtful Nashville students became leaders in one of history’s most impressive—and successful—mass movements, as they threw their bodies, their very lives, on the line to end segregation in the South. The Shadows of Youth: The Remarkable Journey of the Civil Rights Generation, by Andrew B. Lewis, is a new look at this era, examining it through the lens of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and its leaders—Diane Nash, John Lewis, Bob Moses, Stokely Carmichael, Marion Barry, Bob Zellner, and Julian Bond.

Nash, Lewis, and Barry, all students in Nashville, were present when SNCC was created in April 1960 to coordinate and broaden the massive civil disobedience that began in February 1960 with lunch-counter sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, and a few weeks later in Nashville. The Nashville students were nicknamed the “seminarians” by others in SNCC, notes Lewis, who is not related to John Lewis. Trained by Jim Lawson, a Vanderbilt divinity student, they viewed the struggle as essentially moral rather than political. Believing in the power of redemption, they were convinced the protesters’ sacrifice would move the hearts of observers, shame even arch-segregationists, and thereby heal a broken society.

By contrast Carmichael, who grew up in an Italian neighborhood of the Bronx and took the subway to Harlem to get his hair cut in a proper black barbershop, and Julian Bond, son of academics and the only black student in his Pennsylvania prep school, both saw the struggle in more political than redemptive terms. Over the long years of grueling field work in difficult and dangerous conditions, that ideological split was the drop of difference that poisoned the communal water, Lewis concludes.

Lewis meticulously traces the path SNCC activists followed—from lunch counters in 1960, to segregated bus waiting rooms during the 1961 Freedom Rides, to voter registration drives in Macomb, Mississippi, and Albany, Georgia, in 1961 and 1962, through the Birmingham children’s marches in 1963, through the deadly Freedom Summer of 1964. They refused bail when they were arrested, read Gandhi and sang freedom songs in their jail cells, and manned new WATS lines 24/7 to respond to calls for help from the field. They endured brutal beatings, even murder, but invariably countered abuse, attack and arrest by throwing even more bodies into the fray. One of their favorite catchphrases: “Where is your body?”

Believing in the power of redemption, they were convinced the protesters’ sacrifice would move the hearts of observers, shame even arch-segregationists, and thereby heal a broken society.

Lewis credits the youthful energy of the SNCC leaders with driving the civil-rights movement farther and faster than their elders would ever have dreamed or dared. Quoting one SNCC organizer, Lewis notes that Martin Luther King Jr., whom he portrays as distant from the ground war, couldn’t “let a SNCC person be more willing to go to jail than himself.” Self-aggrandizing and overly cautious, King wavered from the open confrontations SNCC activists forced upon him, up to and including the bloody March 1965 confrontation on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

Within SNCC itself, Lewis maintains that the fatal rift opened in 1966 when an all-night power struggle at a SNCC retreat ended with John Lewis ousted as president and Stokely Carmichael in charge. Within weeks Carmichael stepped up on a Civil War monument in Greenwood, Mississippi, espoused Black Power, and the unraveling of SNCC as a unified activist organization began. Lewis details the disillusionment, anguish, and severe depression many of SNCC’s most dedicated members suffered in the aftermath of Carmichael’s term—and then H. Rap Brown’s—as head of SNCC. Bob Moses “once said that time in the movement was compressed and that one month of Mississippi time was like a year of real time,” Lewis writes. “Movement time was catching up with SNCC.”

He follows the core group through the shadows and then finally out the other side. Carmichael spent nearly his whole life in Africa. Nash drifted back to her hometown of Chicago and lived with her two children after her marriage to fellow Nashville SNCC member James Bevel collapsed. She was rescued from obscurity when PBS featured her in its Eyes on the Prize documentary. To avoid the draft, Bob Moses fled the United States, first to Canada and then to Tanzania, where he lived until President Carter offered amnesty to Vietnam-era draft dodgers.

Lewis, Barry and Bond, of course, successfully turned to politics. Lewis focuses closely on the bitter 1986 Georgia congressional race between John Lewis and Julian Bond, with whom the author has a personal friendship. (Lewis is also the author of Gonna Sit at the Welcome Table: A Documentary History of the Civil Rights Movement, which he co-authored with Bond.) He repeatedly jabs Lewis’s mythic reputation with darts about his over-sensitivity, ambition, and jealousy. This animus toward Lewis and King somewhat mars the credibility of the narrative, especially as John Lewis’s name is missing from the list of former SNCC members that he interviewed.

Lewis, Barry and Bond, of course, successfully turned to politics. Lewis focuses closely on the bitter 1986 Georgia congressional race between John Lewis and Julian Bond, with whom the author has a personal friendship. (Lewis is also the author of Gonna Sit at the Welcome Table: A Documentary History of the Civil Rights Movement, which he co-authored with Bond.) He repeatedly jabs Lewis’s mythic reputation with darts about his over-sensitivity, ambition, and jealousy. This animus toward Lewis and King somewhat mars the credibility of the narrative, especially as John Lewis’s name is missing from the list of former SNCC members that he interviewed.

The Shadow of Youth lacks the immediacy and narrative sweep of David Halberstam’s The Children, which follows the same players through the same events, many of which Halberstam witnessed as a reporter for The Tennessean. And unlike Taylor Branch’s trilogy on the civil rights era, which lionizes King, Lewis focuses instead on the young activists and the way the early rush of triumph and sacrifice at SNCC affected the rest of their lives. Still, Lewis’s writing is both moving and meticulous, although not academic, in detailing the profound influence this band of brothers and sisters had on the civil-rights movement. His revisiting of the people and events of that time on the eve of the fiftieth anniversary of the lunch-counter sit-ins is welcome, though it’s a shame the publisher failed to include historical photographs.

The trip SNCC founders took, from the early “freedom highs” when “the civil rights movement tapped the energies—the careless expectations and raw idealism—of its own youth” to maturation and middle age, is a classic cycle of youthful hope turning to disillusionment. Wisely, Lewis takes their stories through the shadows cast by their youthful experiences into the years of their renewed influence, wisdom, and acceptance. He narrates this journey with clarity and passion: “How this ragtag band with little money, no obvious power, painfully little help from the federal government, and the entire white South out to get them, played a starring role in the demise of legal segregation is one of the great adventure stories of American history.”

Tagged: Nonfiction