Unbroken

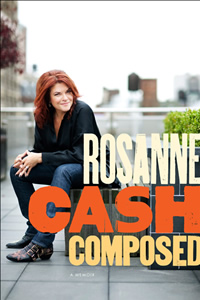

In a beautiful new memoir, Rosanne Cash tells her own story

Composed, the new memoir by Rosanne Cash, could just as easily be titled A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman. Whether James Joyce’s novel served as a template (one of Cash’s favorite words) for it, Composed invites comparisons to Joyce’s coming-of-age masterpiece.

Written with grace, generosity, and restraint, the memoir chronicles Cash’s struggle to come to terms with her famous musical pedigree while simultaneously creating an enduring artistic legacy of her own, separate but still threaded to the past: “I belong to an extended family of musicians whose members sprawl across generations,” she writes. Cash has a songwriter’s gift for settling on the perfect word, and sprawl is just that: her family—including her father, Johnny Cash; her uncle, Tommy Cash; and her stepmother’s family, the Carters, who practically invented bluegrass—provided a musical education that began the day after Cash graduated from high school, when she hit the road as part of her father’s caravan, traveling the world. She learned to play guitar from June Carter’s sister Helen, from Mother Maybelle Carter, and from Carl Perkins. Not a bad way to spend a summer vacation.

“At the heart of all country music lies family, lies a devotion to exploring the bonds of blood ties,” she writes. But for Cash herself those bonds carried enormous and sometimes oppressive burdens. Growing up “a withdrawn, pudgy girl with a swollen face and a foggy head,” she found it nearly impossible to emerge from her father’s shadow or live up to her mother’s standards of beauty. A daydreamer with an independent streak, she recalls trapping tarantulas in jars because it gave her a “sense of power”: she could study the spider as long as she liked, but “it could do nothing to hurt me.”

“At the heart of all country music lies family, lies a devotion to exploring the bonds of blood ties,” she writes. But for Cash herself those bonds carried enormous and sometimes oppressive burdens. Growing up “a withdrawn, pudgy girl with a swollen face and a foggy head,” she found it nearly impossible to emerge from her father’s shadow or live up to her mother’s standards of beauty. A daydreamer with an independent streak, she recalls trapping tarantulas in jars because it gave her a “sense of power”: she could study the spider as long as she liked, but “it could do nothing to hurt me.”

For many years, Rosanne Cash also kept her world, her emotions, and her ambitions under a tightly sealed lid. She always knew she wanted to write and she knew she had a gift for words. A seventh-grade writing assignment produced an ambitious and lovely metaphor that years later found its way into a song and into the book’s conclusion. (Sorry, no spoilers here.) But a need to escape “the merciless exposure of a public life,” combined with a natural wanderlust, led her to Los Angeles (where she studied Method acting at the Lee Strasberg Institute), London, Germany, and eventually, at her father’s beckoning, back home again.

Despite the impulse to write a memoir, Cash is fiercely private and has a strong need to protect the privacy of her friends and family, as well. Readers interested in gossip, music-industry backbiting, or details of Johnny Cash’s addiction or marriage to June Carter will not find it here. Cash escaped to Paris when the movie Walk the Line was released: she had no interest in “a new version of my father’s drug addiction and the collapse of my nuclear family, the two central catastrophic events of my childhood, which have cast their long shadows over my life since.” Her own frustration with her father’s addictions and long absences is evident at times, but so is her understanding: “I’d spent enough time behind the curtains to not have any illusions about a performer’s life being one of glamour and excitement.”

For Cash, performing her own songs was a secondary ambition: “I am first and foremost a songwriter,” she writes, and she remains her own harshest critic. By 1976, she remembers, “I had not yet written a good song … and wanted desperately to break through to a level of craft that I worshipped in the songs of Guy Clark, Mickey Newberry, and Townes Van Zant.” Almost ten years later, with her album Rhythm and Romance at number-one on the country charts, she finally felt she had composed some of “her best songs to date” but still could not silence the fretful critic inside her. The night she received BMI’s award for most-performed song of the year, “Hold On,” she went home and “pulled apart the lyrics … until I determined that it did not deserve the award in the least.” She could be equally critical of what she now calls her “authentic, but extremely personal” singing voice, though her “ambivalent relationship” with her own vocal imperfections linger: “[I]t was undependable, embarrassing at times, not enough, not right”—a feeling that comes, in part, from the extraordinary singers she grew up admiring and who were part of her father’s circle of musical friends, among them Patsy Cline and Tammy Wynette.

For Cash, performing her own songs was a secondary ambition: “I am first and foremost a songwriter,” she writes, and she remains her own harshest critic. By 1976, she remembers, “I had not yet written a good song … and wanted desperately to break through to a level of craft that I worshipped in the songs of Guy Clark, Mickey Newberry, and Townes Van Zant.” Almost ten years later, with her album Rhythm and Romance at number-one on the country charts, she finally felt she had composed some of “her best songs to date” but still could not silence the fretful critic inside her. The night she received BMI’s award for most-performed song of the year, “Hold On,” she went home and “pulled apart the lyrics … until I determined that it did not deserve the award in the least.” She could be equally critical of what she now calls her “authentic, but extremely personal” singing voice, though her “ambivalent relationship” with her own vocal imperfections linger: “[I]t was undependable, embarrassing at times, not enough, not right”—a feeling that comes, in part, from the extraordinary singers she grew up admiring and who were part of her father’s circle of musical friends, among them Patsy Cline and Tammy Wynette.

Cash’s first studio collaboration with then-husband Rodney Crowell produced the tentative but boldly named album Right or Wrong, which was followed by a series of successful albums, number-one singles, a Grammy for Best Female Country Vocal Performance (for “I Don’t Know Why You Don’t Want Me”), and three daughters. (She also helped to raise Crowell’s daughter from his first marriage.) King’s Record Shop solidified her stature as an artist, but it also made her miserable. “I wanted to be in the trenches,” she writes, “where the inspiration was.” Because she’d written only three songs for King’s Record Shop, she felt its success was “hollow,” despite its four number-one singles, a ground-breaking achievement for a woman in the music industry.

Interiors, Cash’s most contemplative and, to her mind, most “country” album quietly introduced a new musical direction, one which she charted herself, writing or co-writing all the songs and serving for the first time as the album’s producer. “We can’t do anything with this,” her record company’s A&R person announced. Shortly after its release in 1990, Cash moved to New York with her girls and a new label deal, but without her husband. Interiors failed to produce any number-one singles, but it achieved critical acclaim. In New York, she reveled in the making of a new “elemental” album, The Wheel, but the rumors “in the press or among my friends” about her reasons for leaving Nashville and its tight music community wounded her. Again she took solace from her writing: “Work, for me, is redemption.”

The process of remembering is never linear. One image conjures up another, sometimes in a fragmented, messy fashion. But Cash’s memoir is striking in its fluid construction. She reaches to the past to make sense of the present as easily and confidently as she would reach for a book or a cup of tea. She has a masterful command of and love for language, its sound and its poetry.

It was perhaps inevitable that Rosanne Cash would write a memoir, but it makes sense that she waited so long to commit her memories to a narrative form. In 2003 she wrote and delivered the eulogies for both her stepmother and father. In 2005, her mother died on Cash’s fiftieth birthday. In 2007, she had brain surgery and recovered fully. Her most recent album—last year’s The List, a recording of songs her father believed were essential to appreciate, learn from, and assimilate—began as a way to experience her father’s “musical genealogy” and her own. During the recording process, she writes, she discovered she was making the record more for her children than for herself or for “the honor of my ancestors.”

With Composed, Rosanne Cash comes full circle, embracing family, tradition, the past and the present, and the unexpected gifts of the future. The circle, though fragile perhaps, remains unbroken.

[This review originally appeared on August 9, 2010.]